Copyright © 2002 - 2017 Chopin Society of Atlanta

Journey into the Mystery of Music

Exclusive interview with pianist and harpsichordist

MAGDALENA BACZEWSKA

by Bożena U. Zaremba

Exclusive interview with pianist and harpsichordist

MAGDALENA BACZEWSKA

by Bożena U. Zaremba

Photo: Piotr Powietrzyński

You come from a musical family. Your mother is a pianist, your father used to sing in the Silesian Philharmonic choir, and your two sisters are musicians. Looks like your family played an important role in who you are now.

Absolutely. The fact that in my childhood, even during a nap, I heard my mom practice on the piano definitely shaped my interest in music. My mom is a walking music encyclopedia. I have always been able to ask her any question. Besides, our home was filled with books on music. Music really filled 99 percent of our lives. We spent all of our free time on music making, going to concerts, and discussing music.

Was your career, in a sense, chosen for you?

Absolutely. The fact that in my childhood, even during a nap, I heard my mom practice on the piano definitely shaped my interest in music. My mom is a walking music encyclopedia. I have always been able to ask her any question. Besides, our home was filled with books on music. Music really filled 99 percent of our lives. We spent all of our free time on music making, going to concerts, and discussing music.

Was your career, in a sense, chosen for you?

Maybe, but I fell in love with music and with playing the piano at a very early age. When I was five, I started piano lessons with Mrs. Jadwiga Górecka, wife of late Henryk Górecki*, and she immediately developed my responsiveness to sound and a need for listening. Thanks to her motherly care, if you will, I soon became confident that music would grow to be the center of my life and I could not imagine doing anything else.

Didn’t you feel you were missing something?

Sometimes, when I looked out of the window and saw girls from my neighborhood playing outside, I was sorry I could not join them, but I also remember being proud every time I took the beginner’s sheet music and walked to my piano lesson. I felt I was doing something special. Besides, I always enjoyed studying. My sisters still call me a nerd [laughs]. I was always fascinated by foreign languages. My grandmother taught me German quite early; then came English. I know seven languages and am currently learning Chinese at Columbia University.

When you were sixteen, you were offered the opportunity to study in the U.S. and you left Poland. Was the adjustment hard?

In fact, it was easier than for some of my colleagues. My roommate, who was from Ohio, experienced a much stronger culture shock than I did. I was stunned, however, by the astronomical prices. I could not earn money at that time, and during those first years, my parents spent all their savings to support me. The thought of how much they had to sacrifice to pay for my expenses was difficult for me.

The expenses were not covered by your scholarship?

No. Had I gone to a different school, outside of New York, it may have been easier, but Professor Rose, who invited me to study [at Mannes College] is not only a wonderful music teacher, but also a mentor, and I could not imagine studying anywhere else. Anyway, New York appealed to me from the very beginning, and I am still enchanted by this city, even though it is noisy and crowded. It has this magic and energy, and I am always happy to come back.

How do you cope with the fierce competition in New York?

If you decide to live in this city, you need to give in to the idea that you will inevitably participate in a kind of a rat race. They say that it is difficult to throw a hat in New York without hitting a pianist, but I have gotten used to it and believe that if you love music so much that it becomes the integral part of your life, there will be a place for everyone.

How do you compare musical education in Poland and the U.S.?

On the one hand, I was so well prepared that I was allowed to participate in advanced classes, such as ear training or theory, right away. On the other hand, I was accustomed to “standing to attention” at Polish schools, and here, all of a sudden, teachers became our partners, whom we did not have to fear. We were able to ask questions and freely express our opinion. This was new to me and a bit shocking perhaps, because I was not used to class participation at this level.

You are recognized as both a wonderful pianist and harpsichordist. It is commonly known that the different technique can be an obstacle in playing both instruments, but what are the advantages?

It is true that the technique is so different that it took me years to learn to switch from one instrument to the other with ease. As far as the advantages are concerned, the harpsichord opens our eyes and ears to different aesthetics. As pianists, we are encouraged to be as true to the musical score as possible, while harpsichordists have more freedom for improvisation, creativity, and taste.

In addition to being a concert pianist and a teacher, you have a Doctor of Musical Arts degree. Why did you decide to continue studying?

Being a nerd [laughs], I had no other option. I wanted to study as long as possible; I craved for deeper knowledge about the secrets of music. On top of that, I fell in love with teaching. Both my mom and my father are teachers, and I must have it in my genes. Teaching gives me a sense of fulfillment, and I feel I am constantly being granted this energy by my students, who are hungry for knowledge to the same extent that I am. I decided to go to graduate school to become the best teacher I can be.

Your doctoral dissertation** deals with the influence of oratory on pianistic interpretation.

That’s correct. Oratory together with communication are the key aspects of my thesis. Bach’s music is often perceived as something mechanical and didactic. Of course, a lot of his music was written for educational purposes, but this music has essence and spirit, and it is wrong to look at it in a simplistic and uniform way. Bach wanted to reach out to people, and he possessed an extensive knowledge of rhetoric and the art of speaking to people in a convincing way. It is worth remembering that during the Baroque era, the general sense of piety or religiousness was much stronger than it is today. St. Augustine considered music to be divine; accordingly, Bach, as a very religious person, treated music as a form of meditation and prayer, as well as a way to worship God.

Music in church still has the same role.

Yes, but let’s remember that 300 years ago, the church was the only place where people could listen to music. Very few had access to the royal court, but everyone could come to church and experience the highest form of music.

Cantabile, which has as important a place in your research as communication, is an aesthetic quality, so do you discuss phrasing? Without it, we are talking only about a progression of beautiful sounds.

Of course. Every phrase forms a sentence, and a combination of even two notes forms a word. If we want to emphasize an important word, we pause before it in order to make it more conspicuous. This is essential in speaking and in singing. It should be essential in music, too.

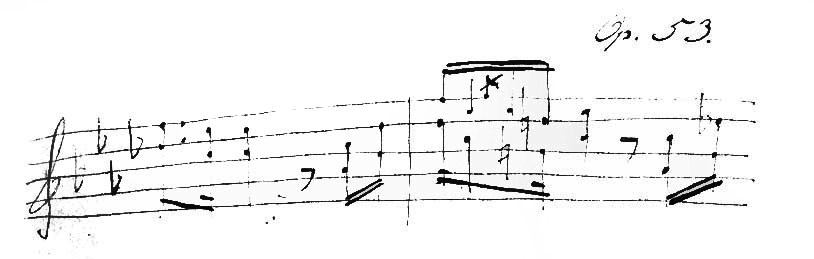

So, it isn’t the same cantabile as in Chopin’s music?

The word cantabile in Chopin’s music comes from operatic bel canto style, which means long, juicy phrases, while in Bach, cantabile refers to the declamatory style. We know that Chopin loved opera and bel canto singing. He even encouraged his students to learn to sing, claiming that thanks to singing and to correct breathing, one can truly become a good musician and create a sound that is pleasing to the ear. Everything else he considered “barking” [laughs]. But of course, successive beautiful sounds do not communicate anything, so the amount of emotion we put into each phrase is very important. In the master classes I participated in, I had an opportunity to play for many fine pianists, who often emphasized that each phrase needs to convey something, needs to have some emotion assigned to it, and that this should be deliberate.

Let’s talk some more about Chopin. What do you admire most about his music?

Oh, I could talk forever [laughs].

I am all ears.

There is a certain quality in his music that grows on you and lets you discover something new every day. In his music, there is an incredible simplicity, under which exist those layers of elegance, craft, and sophistication. His music is completely universal, because it is simple enough to appeal to our hearts and to people who are not musically trained, but at the same, so complex that for a musicologist, it can become a lifetime project. Chopin’s music is a universe of its own.

Can such in-depth knowledge that you have stand in the way of playing?

Sometimes you can hear musicians who are so consumed with theoretical issues that they forget that music should first of all speak to our hearts. In some instances, a lack of musical training is bliss, for example for folk singers, who seem to have no idea with what intervals, rhythm, or time signature they sing. They often do it with more freedom and abandon than trained musicians, for whom the whole thing seems complicated and uncomfortable.

How does this relate to the listeners?

It depends. At times I get annoyed by certain performers’ ignorance or lack of interest in studying the score thoroughly. But this does not mean that musical training is necessary for being moved by music.

You have recorded a series of three CDs, Music for Dreams, in collaboration with a specialist for sleeping disorders. How did you become interested in this subject?

At one of my New York performances of Bach’s Goldberg Variations, I shared with the audience the fact that the piece was written for Count Kaiserling, who was an insomniac. After the concert, Dr. Stern, who specializes in sleep disorders, came up to me and asked me if I would be interested in a collaboration on a CD with music that could help his patients relax before going to bed. I was a bit surprised, because I always try to stimulate my audience, rather than put them to sleep [laughs]. Still, I agreed, and it turned out to be a very interesting challenge***. The demand was so great that I recorded two more CDs, and now Music for Dreams is being played in almost 30,000 households. This project is also a love story: Dr. Stern later became my husband.

Another interesting project of yours is teaching music appreciation to senior citizens. Can you tell me more about it?

These online classes are for seniors who live in New York. I play compositions by a composer, often chosen by the senior, and then we talk via teleconference. This is all about interaction, as it is important to keep seniors mentally active. These are very interesting people—some of them are retired opera singers, actors or writers—and the discussions are very stimulating for all.

During your recitals, you have a custom of talking about the music or the composer. Can we count on that in Atlanta?

Absolutely, with great pleasure. It is important for me to have the audience take away from this experience as much as possible. Such an introduction helps them get more involved and feel more included. Sometimes one sentence will suffice to take the listener on a journey into the mystery of music.

*Henryk Górecki (1933–2010), a renowned Polish composer of contemporary classical music.

**Title: “In Search of Bach’s Cantabile: The Role and Aspects of Oratory and Singing in Keyboard Interpretation”

***Additional information about the creative process behind this project and the relationship between the human brain and music can be read here: https://store.cdbaby.com/cd/magdalenabaczewska1

Didn’t you feel you were missing something?

Sometimes, when I looked out of the window and saw girls from my neighborhood playing outside, I was sorry I could not join them, but I also remember being proud every time I took the beginner’s sheet music and walked to my piano lesson. I felt I was doing something special. Besides, I always enjoyed studying. My sisters still call me a nerd [laughs]. I was always fascinated by foreign languages. My grandmother taught me German quite early; then came English. I know seven languages and am currently learning Chinese at Columbia University.

When you were sixteen, you were offered the opportunity to study in the U.S. and you left Poland. Was the adjustment hard?

In fact, it was easier than for some of my colleagues. My roommate, who was from Ohio, experienced a much stronger culture shock than I did. I was stunned, however, by the astronomical prices. I could not earn money at that time, and during those first years, my parents spent all their savings to support me. The thought of how much they had to sacrifice to pay for my expenses was difficult for me.

The expenses were not covered by your scholarship?

No. Had I gone to a different school, outside of New York, it may have been easier, but Professor Rose, who invited me to study [at Mannes College] is not only a wonderful music teacher, but also a mentor, and I could not imagine studying anywhere else. Anyway, New York appealed to me from the very beginning, and I am still enchanted by this city, even though it is noisy and crowded. It has this magic and energy, and I am always happy to come back.

How do you cope with the fierce competition in New York?

If you decide to live in this city, you need to give in to the idea that you will inevitably participate in a kind of a rat race. They say that it is difficult to throw a hat in New York without hitting a pianist, but I have gotten used to it and believe that if you love music so much that it becomes the integral part of your life, there will be a place for everyone.

How do you compare musical education in Poland and the U.S.?

On the one hand, I was so well prepared that I was allowed to participate in advanced classes, such as ear training or theory, right away. On the other hand, I was accustomed to “standing to attention” at Polish schools, and here, all of a sudden, teachers became our partners, whom we did not have to fear. We were able to ask questions and freely express our opinion. This was new to me and a bit shocking perhaps, because I was not used to class participation at this level.

You are recognized as both a wonderful pianist and harpsichordist. It is commonly known that the different technique can be an obstacle in playing both instruments, but what are the advantages?

It is true that the technique is so different that it took me years to learn to switch from one instrument to the other with ease. As far as the advantages are concerned, the harpsichord opens our eyes and ears to different aesthetics. As pianists, we are encouraged to be as true to the musical score as possible, while harpsichordists have more freedom for improvisation, creativity, and taste.

In addition to being a concert pianist and a teacher, you have a Doctor of Musical Arts degree. Why did you decide to continue studying?

Being a nerd [laughs], I had no other option. I wanted to study as long as possible; I craved for deeper knowledge about the secrets of music. On top of that, I fell in love with teaching. Both my mom and my father are teachers, and I must have it in my genes. Teaching gives me a sense of fulfillment, and I feel I am constantly being granted this energy by my students, who are hungry for knowledge to the same extent that I am. I decided to go to graduate school to become the best teacher I can be.

Your doctoral dissertation** deals with the influence of oratory on pianistic interpretation.

That’s correct. Oratory together with communication are the key aspects of my thesis. Bach’s music is often perceived as something mechanical and didactic. Of course, a lot of his music was written for educational purposes, but this music has essence and spirit, and it is wrong to look at it in a simplistic and uniform way. Bach wanted to reach out to people, and he possessed an extensive knowledge of rhetoric and the art of speaking to people in a convincing way. It is worth remembering that during the Baroque era, the general sense of piety or religiousness was much stronger than it is today. St. Augustine considered music to be divine; accordingly, Bach, as a very religious person, treated music as a form of meditation and prayer, as well as a way to worship God.

Music in church still has the same role.

Yes, but let’s remember that 300 years ago, the church was the only place where people could listen to music. Very few had access to the royal court, but everyone could come to church and experience the highest form of music.

Cantabile, which has as important a place in your research as communication, is an aesthetic quality, so do you discuss phrasing? Without it, we are talking only about a progression of beautiful sounds.

Of course. Every phrase forms a sentence, and a combination of even two notes forms a word. If we want to emphasize an important word, we pause before it in order to make it more conspicuous. This is essential in speaking and in singing. It should be essential in music, too.

So, it isn’t the same cantabile as in Chopin’s music?

The word cantabile in Chopin’s music comes from operatic bel canto style, which means long, juicy phrases, while in Bach, cantabile refers to the declamatory style. We know that Chopin loved opera and bel canto singing. He even encouraged his students to learn to sing, claiming that thanks to singing and to correct breathing, one can truly become a good musician and create a sound that is pleasing to the ear. Everything else he considered “barking” [laughs]. But of course, successive beautiful sounds do not communicate anything, so the amount of emotion we put into each phrase is very important. In the master classes I participated in, I had an opportunity to play for many fine pianists, who often emphasized that each phrase needs to convey something, needs to have some emotion assigned to it, and that this should be deliberate.

Let’s talk some more about Chopin. What do you admire most about his music?

Oh, I could talk forever [laughs].

I am all ears.

There is a certain quality in his music that grows on you and lets you discover something new every day. In his music, there is an incredible simplicity, under which exist those layers of elegance, craft, and sophistication. His music is completely universal, because it is simple enough to appeal to our hearts and to people who are not musically trained, but at the same, so complex that for a musicologist, it can become a lifetime project. Chopin’s music is a universe of its own.

Can such in-depth knowledge that you have stand in the way of playing?

Sometimes you can hear musicians who are so consumed with theoretical issues that they forget that music should first of all speak to our hearts. In some instances, a lack of musical training is bliss, for example for folk singers, who seem to have no idea with what intervals, rhythm, or time signature they sing. They often do it with more freedom and abandon than trained musicians, for whom the whole thing seems complicated and uncomfortable.

How does this relate to the listeners?

It depends. At times I get annoyed by certain performers’ ignorance or lack of interest in studying the score thoroughly. But this does not mean that musical training is necessary for being moved by music.

You have recorded a series of three CDs, Music for Dreams, in collaboration with a specialist for sleeping disorders. How did you become interested in this subject?

At one of my New York performances of Bach’s Goldberg Variations, I shared with the audience the fact that the piece was written for Count Kaiserling, who was an insomniac. After the concert, Dr. Stern, who specializes in sleep disorders, came up to me and asked me if I would be interested in a collaboration on a CD with music that could help his patients relax before going to bed. I was a bit surprised, because I always try to stimulate my audience, rather than put them to sleep [laughs]. Still, I agreed, and it turned out to be a very interesting challenge***. The demand was so great that I recorded two more CDs, and now Music for Dreams is being played in almost 30,000 households. This project is also a love story: Dr. Stern later became my husband.

Another interesting project of yours is teaching music appreciation to senior citizens. Can you tell me more about it?

These online classes are for seniors who live in New York. I play compositions by a composer, often chosen by the senior, and then we talk via teleconference. This is all about interaction, as it is important to keep seniors mentally active. These are very interesting people—some of them are retired opera singers, actors or writers—and the discussions are very stimulating for all.

During your recitals, you have a custom of talking about the music or the composer. Can we count on that in Atlanta?

Absolutely, with great pleasure. It is important for me to have the audience take away from this experience as much as possible. Such an introduction helps them get more involved and feel more included. Sometimes one sentence will suffice to take the listener on a journey into the mystery of music.

*Henryk Górecki (1933–2010), a renowned Polish composer of contemporary classical music.

**Title: “In Search of Bach’s Cantabile: The Role and Aspects of Oratory and Singing in Keyboard Interpretation”

***Additional information about the creative process behind this project and the relationship between the human brain and music can be read here: https://store.cdbaby.com/cd/magdalenabaczewska1