Copyright © 2002 - 2018 Chopin Society of Atlanta

On Fire

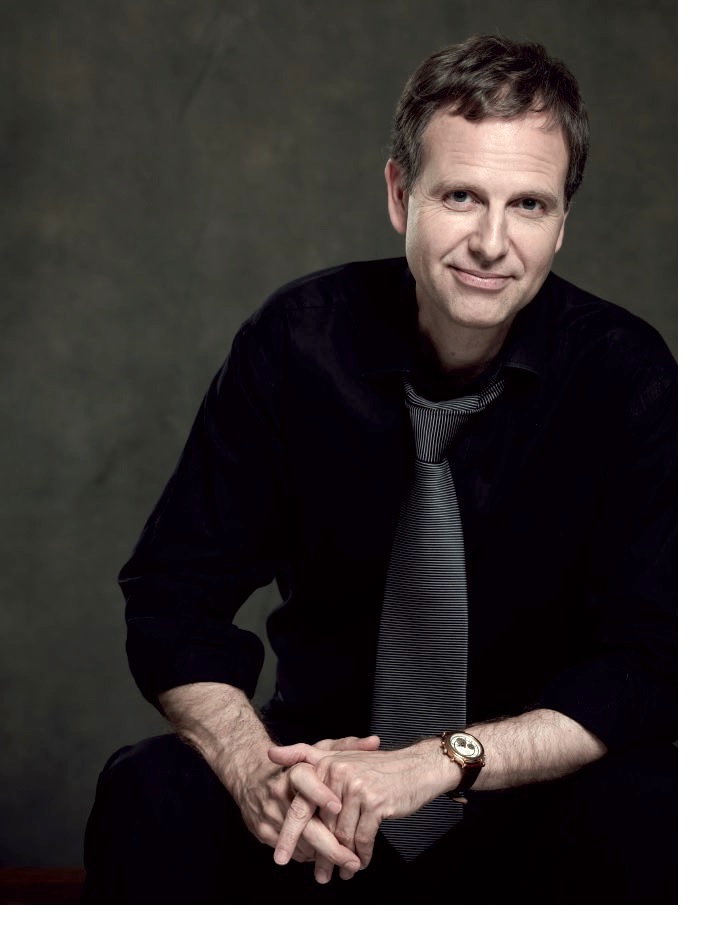

Exclusive Interview with Kevin Kenner

winner of the 1990 Fryderyk Chopin International Piano Competition in Warsaw, Poland, winner of the Bronze Medal at the Tchaikovsky International Competition in Moscow, and Assistant Professor of Keyboard Performance at University of Miami’s Frost School of Music

By Bożena U. Zaremba

Bożena U. Zaremba: So it seems you have settled down.

Kevin Kenner: I think so. Miami is definitely my main home now, and my teaching job at the Frost School of Music is my main occupation. I really enjoy it. At this point of my life, teaching is just as meaningful as performing.

BUZ: Why Miami?

KK: I have had friends in Miami since 1990, when I participated in the Chopin Piano Competition organized by the Chopin Foundation. Being a prize winner of that Competition, I returned to Miami many times. In 2015, I was at the same piano competition, this time as a juror, and a good friend of mine told me there was an opening at UM. I asked my girlfriend, who is Polish, if she would come to Miami just for a year, just to try living in another country to see

Exclusive Interview with Kevin Kenner

winner of the 1990 Fryderyk Chopin International Piano Competition in Warsaw, Poland, winner of the Bronze Medal at the Tchaikovsky International Competition in Moscow, and Assistant Professor of Keyboard Performance at University of Miami’s Frost School of Music

By Bożena U. Zaremba

Bożena U. Zaremba: So it seems you have settled down.

Kevin Kenner: I think so. Miami is definitely my main home now, and my teaching job at the Frost School of Music is my main occupation. I really enjoy it. At this point of my life, teaching is just as meaningful as performing.

BUZ: Why Miami?

KK: I have had friends in Miami since 1990, when I participated in the Chopin Piano Competition organized by the Chopin Foundation. Being a prize winner of that Competition, I returned to Miami many times. In 2015, I was at the same piano competition, this time as a juror, and a good friend of mine told me there was an opening at UM. I asked my girlfriend, who is Polish, if she would come to Miami just for a year, just to try living in another country to see

Please read our 2007 interview with Kevin Kenner, who spoke at length about Chopin and his music

if we like it. So it was a kind of experiment. After having lived in Europe for twenty-six years, I thought it would be fun. I actually had no intention of staying in Miami for long, but I loved the environment and the company of friends, and the job was great, so we decided to stay. Everything there is ideal for me, and probably I will stay there for the rest of my life.

BUZ: Last summer, you presented the first Chopin Academy and Festival at the Frost School of Music. How did you come up with the idea?

KK: At that competition in 2015, having had just minimal contact with the contestants, I realized I had this desire not to just judge them and give them a score, but to really work with them. We have some wonderfully talented musicians in the U.S., and I would like to share with them what I know about Chopin. I am in a very good position here in Miami, with the support of the Chopin Foundation and because the Frost School of Music is a very progressive and forward-looking organization, open to all kinds of new ideas. Also because of my position in the world of music as a specialist of the music of Chopin, it all came together. The experiment went quite well, and I have every intention of continuing it. I hope Miami will become a center for education in Chopin’s music.

BUZ: What is the purpose of the Festival?

KK: The main purpose was the Academy, not the concerts. The Academy gives an opportunity for young pianists to meet with some of the most respected Chopin’s specialists, have lessons with them, meet with scholars, and attend workshops and lectures. Of course, students also perform at the Festival, which gives them performing experience. And with so many teaching artists who are performers as well, it was natural to create a surrounding festival to listen to these great artists in performance, also of great benefit to our students. So the Festival’s purpose is primarily educational.

BUZ: You sound passionate about teaching.

KK: I have always enjoyed teaching. My first teaching position was in London in 1999, where I taught for eleven years. I became more and more passionate about teaching when I started to judge at piano competitions. I wanted to make sure that these talented pianists have every opportunity to develop and preserve classical music for next generations. I am not going to be here forever, but I see it as my mission to pass on my knowledge and expertise to the younger generation and leave something meaningful behind. I want to inspire them and share with them ideas which will hopefully take root and help them create ideas of their own. It is just very rewarding to see that. And it gives me a lot of joy when I see their successes.

BUZ: What are the most important things you want to pass on to your students? Technique? Interpretation? Comprehensive and deep knowledge of the composer’s life and times?

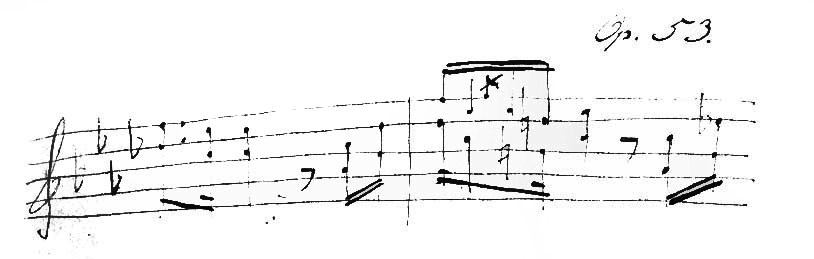

KK: It is all of those things. What is most rewarding about teaching is more ambiguous, not quite so concrete. I would say it has more to do with helping students discover what’s inside of them. The teacher has an obligation to teach the whole process of learning, including technique and inner discipline, but in the end, it is some kind of awakening that occurs in the student, and a good teacher understands that there is no one method that can spark that awakening. It is very individual, and sometimes it doesn’t work. I have often thought there are good and bad teachers, but now I believe there are good and bad relationships between teachers and students. It is hard to find the perfect combination. When teacher and student can understand each other, as in any good relationship, there is something that can bring out the best in the other person. That’s the goal. It is not just one thing. It is not just interpretation. That is certainly a part of it because interpretation entails perfecting your study of a historical document—the musical score, unless, of course, you are playing contemporary music—and understanding it within the context in which it was written. Interpretation isn’t about injecting one’s emotions into the music. It is more about discovering what is inherently in the music and projecting that. This discovery is only realized through the ability to look very carefully at the score and find a way to refresh or resurrect the essence of the material into a performance that works in today’s context. After the recent Chopin competition on period instruments, I started to rethink what one does as an interpreter. Do we look back and try to recreate the way Chopin played himself, or are we looking to adapt the original ideas to a modern context and create something new? It is a question that is hard to answer, but it is worth considering.

BUZ: What if you have played a particular piece several times already? How do you make it sound fresh?

KK: The answer, again, is not straightforward. If I go to an art gallery and look at paintings, come back, and make music again, the experience of looking at the artwork could have awakened something in my soul, which may then have an effect on the way I experience the score afterwards. We, as artists, always have to be alert emotionally and intellectually. We have to keep on our toes. An interpretation stagnates if the pianist is not aware of what he or she is actually doing, or when the pianist stops listening and allowing the music to speak. So any kind of creative activity—whether it is going to an art gallery or reading literature—can assist the artist in keeping the interpretive process alive. I could also say that going back to the score and studying it carefully oftentimes refreshes my memory or even helps discover things I have never noticed before. Earlier this August, for instance, when I recorded Chopin’s concertos again, I made it a point to look at all the first editions in order to discover the source material anew, to analyze and question every choice I make, so that when I do interpret, it is a choice rather than some subconscious auto-pilot which takes over and leads to stagnation.

BUZ: Do you then encourage your students to do things outside of music?

KK: Of course. That is one of the reasons why I chose to teach at a university, because this is an institution that encourages well-rounded education and gives students an opportunity to take art classes, for instance. I have one student who is taking a painting class this term. There is so much you can learn by getting involved in all the humanities. It all overlaps. Recently, I have taken up an interest in Goethe, who speaks of music in terms of architecture. So when I sit down to work on Chopin’s Ballade, because I was reading Goethe and thinking of architecture, I can’t help but think of the architecture of sound, how the composer creates certain moments of tension in music and holds everything together, and how you need to have certain resolutions of that tension. The difference is that architecture does not have the element of time that music does. You could say that music is liquid architecture, or as Goethe proposed: architecture is frozen music. Anyway, that kind of opening of the mind to new ideas, allowing your imagination to run free and cross-breed can be very inspiring. It can help a student of music interpret in an original way, not just according to some tradition. Tradition is great, but, unfortunately, it can also discourage students from discovering for themselves what lies at the heart of that tradition. In other words, all great pianists do more than just play according to tradition. They create one.

BUZ: On top of that, there is theory. I had a pleasure of attending one of the lectures at your Festival, by Alan Walker1, who presented a fantastic analysis of Chopin’s genius and advice on how to play his music. He talked about a perfect balance between the composer and the pianist’s personality, and according to him, the most fundamental rule of interpreting Chopin’s music is not to break the “11th Commandment,” which he defines as: “Thou shall not fool with Chopin or else he will fool with you.” Do you subscribe to this recommendation?

KK: Absolutely. That is precisely what makes interpretation of Chopin so challenging. His music has a certain fragility. If you push and pull just a little too far, things simply break down. For other composers of the Romantic period—Schubert, Schumann, and Liszt—pushing or pulling too much might actually be encouraged according to Romantic standards. Chopin was rather enigmatic for his time because of his deep interest in the music of the past and his love for Classical principles, for Handel, for instance. In 1829, in one of his letters, he wrote that Handel’s music was close to his image of what he considered to be ideal music. He was not a proponent of the principles of his Romantic contemporaries, which pushed for more individuality and extreme emotions. Chopin was so much more interested in the values of Classicism—the purity of sound and balancing of structure. He was also interested in the early Romantic Italian bel canto opera, which had so much to do not with power and forceful sounds that project through the entire theater, but rather with subtle, delicate phrasing and beautifully controlled singing. If one injects too much of their personality, this can destroy one of the core aesthetic values of Chopin’s music.

BUZ: Professor Walker talked at length about human voice and its connection to Chopin’s music. You should learn to sing to play his music well, he said.

KK: There are good and bad singers [laughs]. It is very useful to learn to sing and to work with singers. One should also remember that when Chopin employed the vocal techniques of the 19th century, what he really valued was the control of the voice and the beautiful embellishments of the bel canto-style singers.

BUZ: And then there is breathing and phrasing.

KK: Correct. Great singers can breathe in such a subtle and beautifully controlled way that we don’t even realize that they are breathing. Chopin himself said that the lifting of the wrist—not the whole arm—was the mechanism for breathing in piano playing. There needs to be this subtle flexibility in music, just like in the limited rubato Chopin spoke of; if you blow the candle too much, you will blow out the flame entirely

BUZ: This year you released a recording of solo piano works by another splendid Polish composer, Ignacy Jan Paderewski, which you performed on his own 1925 Steinway.

KK: I fell in love with that instrument. However, I have to say it was quite a challenge to play it, especially performing large-scale compositions like the sonata and toccata, which are pieces that demand power and clarity. The hammers are larger than in today’s Steinways, and the tone was quite mellow and better suited for works that have a lot of melodic quality. There was something mature, ripe about that instrument; it lacks directness and felt burnished. I must say that after the first day of recording, my hands were almost bleeding [laughs].

BUZ: After your concert in 2011 that featured works by Paderewski, the reviewer described it as your “homage to the tireless energy and spirit of the Polish people.” Last February you played Paderewski again, this time at Carnegie Hall to celebrate the 100th anniversary of Polish independence. What significance did this concert have for you?

KK: Apart from the fact that it was actually the first time that I performed at the Stern Auditorium (I had played at Carnegie Hall before, but never at Stern), it was really a special moment to be playing on the same stage on which this great pianist played. I felt I was transported in history. I have nothing but the greatest respect for Paderewski, not only as a musician but also as a man, as a statesman. He was remarkable. He even offered to pay off his country’s national debt with his own money! There are few politicians today who would do that. And I love his music. So to be able to perform on the stage he loved so dearly and where he often played was such a great honor, and I will remember this as a special moment in my performing career.

BUZ: Paderewski is one of the few classical musicians who got involved in politics, and his role in Poland’s gaining independence is unquestionable.

KK: He was never interested in politics per se. He was living during the times when it was inevitable. He was simply interested in seeing his country not being destroyed and existing as a state. I think politics was not something he particularly enjoyed or sought. He did not have a great desire to be a prime minister of Poland, and it certainly did not last very long. He loved his nation and felt the obligation as a person of repute, of great success and means to use his gifts for the sake of his people. That’s what I love about him. He was more than just a patriot. He believed in the brotherhood of humankind, as did Beethoven. I believe that is why so many people loved him, because he was a human being in the highest sense of the word.

BUZ: Paderewski was significantly influenced by Chopin. Where can we see the traces of the great master?

KK: It is all over the place. First of all, it is the essential “Polishness” of Chopin’s music, which we find in Paderewski, too. Also, he wrote the same forms, such as krakowiak, nocturnes, and pieces that have references to Chopin, not to mention that both Paderewski and Chopin grew up in Poland, then lived far away from the homeland they so longed for. In addition, there is something improvisatory about Paderewski’s compositional style. When you look at his score, the music changes all the time; harmonies are rarely repeated in sections that normally should repeat. He would often perform his music differently from the way he had written it down. It helped me actually understand something about Chopin. That is why we can find different versions of the same work, for example the Waltz Op. 69, No. 2, in which the French edition has significantly different harmonies and rhythms from the English edition. I don’t think either Chopin or Paderewski heard their music in an idealized final form. What we have in their scores are more like sketches or snapshots of a potential interpretation. When I interpret Paderewski, I really try to explore the ideas that are on the page, but I never limit myself to merely what I see. I make quite a few small changes, within the style, of course. I do the same with Chopin’s music, especially with his earlier works. I think these small embellishments or alterations can actually benefit the score and give it greater authenticity. Being completely faithful to the score means more than just playing the notes that are there. In the same way, to not embellish certain passages in Mozart would be contrary to performance practice and counter to his performance style. So I think in this respect, Chopin and Paderewski have very much in common. Their music is very fluid—constantly changing.

BUZ: Have there been any composers since Paderewski who have carried on this tradition?

KK: There were contemporaries to Paderewski who carried that tradition, Rachmaninoff being the greatest. As a pianist he was superior to any other pianist of that time. You hear that freedom and improvisatory quality in his recordings; he does not follow his score particularly closely. After that, you could say that Horowitz belonged to the same kind of thinking, as did Earl Wild, although he was less a composer than an arranger. In Wild’s recording of Paderewski’s Piano Concerto in A minor, Op. 17 you can notice clearly that he takes a lot of liberties, liberties that I think Paderewski would have approved of. Unfortunately, most pianists of the 20th century took a different path. Especially after World War II, the piano world almost sterilized itself; it devalued many of the special qualities that existed in the golden age of pianism.

BUZ: Other forms of music, especially jazz took over that aspect of freedom and improvisation.

KK: Agreed. Chopin and Liszt and many pianists of the 19th century knew how to improvise on any given themes, mostly operatic themes, which were the “standards” at that time. They were the jazz pianists of that age. All jazz musicians know how to improvise on the standards. Leszek Możdżer2 is a wonderful example of a pianist who was trained as a classical pianist and moved to jazz when he finished his studies. I performed with him at a concert themed “Chopin Correspondences,” in which I played certain loops of Chopin themes, and he would improvise over me on the other piano. It was quite extraordinary to listen to the manner in which he heard music. What I found remarkable was that unlike some jazz pianists who have good technical abilities but are limited in areas of tonal color, Leszek Możdżer has such a great sensitivity to those subtle tonal varieties that remind me of Chopin’s tonal world—this delicate quality, purity of sound, an ever-changing palette of colors.

BUZ: I understand that the Frost School of Music has an excellent jazz department

KK: Actually, it is one of the most widely respected jazz music schools in the country. Its faculty has had many accomplished musicians, like Pat Metheny, Gonzalo Rubalcaba, and Shelly Berg, for instance. I encourage my students to learn the principles of jazz because it can have a beneficial effect on their interpretations. Being a good jazz pianist involves strict discipline of understanding harmony and progressions, and inversions, and how particular melodies can be embellished in certain ways. I think that in the next generation, there is going to be a renewal of the improvisational skills that existed in the 19th century. Pianists will be either interested in learning them or perhaps required to employ them. I was recently judging at a Chopin piano competition in Darmstadt, and they introduced—still optional—an improvisational round, with a special prize for the best improvisation. Things are changing in the music world. Another revolution, if you will, is the revival of the interest in period instruments. More and more pianists are looking into the past for a discovery of new interpretations inspired by those instruments. We have seen it with other instruments, with ensembles. Who would now go to a concert of Bach on modern instruments? It is demanded by the audience, because once you have heard this authentic sound, it is difficult to get it out of your system.

BUZ: Is this a reaction to the ever-present digitalization? Haven’t people grown tired of the perfect-pitch, auto-tuned sound, purified by the mastering process?

KK: This is a good observation. As I said earlier, the modern music world sterilized interpretation in many ways, and we demand from modern performance qualities that were completely foreign to the musical values of the 19th century, such as control, evenness, consistency. The rise of the recording industry may have something to do with this. If in the 19th or 18th century a musician played everything evenly and consistently, that musician would be considered very mediocre. Period instruments are fascinating: each of them is so different, and they all have their own personality. No two Pleyels or Erards are the same. Each instrument has its own particular tone and must be approached uniquely, individually. When a pianist plays those instruments, you begin to hear that distinctive sound, and you really start to discover the composer anew, to get into his mind. This new interest in history is on fire. Certainly, it is on fire with me!

1 Dr. Alan Walker (b. 1930) is an English-Canadian musicologist, Professor Emeritus of Music at McMaster University, Canada, known for authoring a three-volume biography of Franz Liszt and Chopin’s new biography Fryderyk Chopin: A Life and Times (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, October 2018).

2 Leszek Możdżer (b. 1971) is a renowned Polish jazz pianist, music producer, and film music composer.

BUZ: Last summer, you presented the first Chopin Academy and Festival at the Frost School of Music. How did you come up with the idea?

KK: At that competition in 2015, having had just minimal contact with the contestants, I realized I had this desire not to just judge them and give them a score, but to really work with them. We have some wonderfully talented musicians in the U.S., and I would like to share with them what I know about Chopin. I am in a very good position here in Miami, with the support of the Chopin Foundation and because the Frost School of Music is a very progressive and forward-looking organization, open to all kinds of new ideas. Also because of my position in the world of music as a specialist of the music of Chopin, it all came together. The experiment went quite well, and I have every intention of continuing it. I hope Miami will become a center for education in Chopin’s music.

BUZ: What is the purpose of the Festival?

KK: The main purpose was the Academy, not the concerts. The Academy gives an opportunity for young pianists to meet with some of the most respected Chopin’s specialists, have lessons with them, meet with scholars, and attend workshops and lectures. Of course, students also perform at the Festival, which gives them performing experience. And with so many teaching artists who are performers as well, it was natural to create a surrounding festival to listen to these great artists in performance, also of great benefit to our students. So the Festival’s purpose is primarily educational.

BUZ: You sound passionate about teaching.

KK: I have always enjoyed teaching. My first teaching position was in London in 1999, where I taught for eleven years. I became more and more passionate about teaching when I started to judge at piano competitions. I wanted to make sure that these talented pianists have every opportunity to develop and preserve classical music for next generations. I am not going to be here forever, but I see it as my mission to pass on my knowledge and expertise to the younger generation and leave something meaningful behind. I want to inspire them and share with them ideas which will hopefully take root and help them create ideas of their own. It is just very rewarding to see that. And it gives me a lot of joy when I see their successes.

BUZ: What are the most important things you want to pass on to your students? Technique? Interpretation? Comprehensive and deep knowledge of the composer’s life and times?

KK: It is all of those things. What is most rewarding about teaching is more ambiguous, not quite so concrete. I would say it has more to do with helping students discover what’s inside of them. The teacher has an obligation to teach the whole process of learning, including technique and inner discipline, but in the end, it is some kind of awakening that occurs in the student, and a good teacher understands that there is no one method that can spark that awakening. It is very individual, and sometimes it doesn’t work. I have often thought there are good and bad teachers, but now I believe there are good and bad relationships between teachers and students. It is hard to find the perfect combination. When teacher and student can understand each other, as in any good relationship, there is something that can bring out the best in the other person. That’s the goal. It is not just one thing. It is not just interpretation. That is certainly a part of it because interpretation entails perfecting your study of a historical document—the musical score, unless, of course, you are playing contemporary music—and understanding it within the context in which it was written. Interpretation isn’t about injecting one’s emotions into the music. It is more about discovering what is inherently in the music and projecting that. This discovery is only realized through the ability to look very carefully at the score and find a way to refresh or resurrect the essence of the material into a performance that works in today’s context. After the recent Chopin competition on period instruments, I started to rethink what one does as an interpreter. Do we look back and try to recreate the way Chopin played himself, or are we looking to adapt the original ideas to a modern context and create something new? It is a question that is hard to answer, but it is worth considering.

BUZ: What if you have played a particular piece several times already? How do you make it sound fresh?

KK: The answer, again, is not straightforward. If I go to an art gallery and look at paintings, come back, and make music again, the experience of looking at the artwork could have awakened something in my soul, which may then have an effect on the way I experience the score afterwards. We, as artists, always have to be alert emotionally and intellectually. We have to keep on our toes. An interpretation stagnates if the pianist is not aware of what he or she is actually doing, or when the pianist stops listening and allowing the music to speak. So any kind of creative activity—whether it is going to an art gallery or reading literature—can assist the artist in keeping the interpretive process alive. I could also say that going back to the score and studying it carefully oftentimes refreshes my memory or even helps discover things I have never noticed before. Earlier this August, for instance, when I recorded Chopin’s concertos again, I made it a point to look at all the first editions in order to discover the source material anew, to analyze and question every choice I make, so that when I do interpret, it is a choice rather than some subconscious auto-pilot which takes over and leads to stagnation.

BUZ: Do you then encourage your students to do things outside of music?

KK: Of course. That is one of the reasons why I chose to teach at a university, because this is an institution that encourages well-rounded education and gives students an opportunity to take art classes, for instance. I have one student who is taking a painting class this term. There is so much you can learn by getting involved in all the humanities. It all overlaps. Recently, I have taken up an interest in Goethe, who speaks of music in terms of architecture. So when I sit down to work on Chopin’s Ballade, because I was reading Goethe and thinking of architecture, I can’t help but think of the architecture of sound, how the composer creates certain moments of tension in music and holds everything together, and how you need to have certain resolutions of that tension. The difference is that architecture does not have the element of time that music does. You could say that music is liquid architecture, or as Goethe proposed: architecture is frozen music. Anyway, that kind of opening of the mind to new ideas, allowing your imagination to run free and cross-breed can be very inspiring. It can help a student of music interpret in an original way, not just according to some tradition. Tradition is great, but, unfortunately, it can also discourage students from discovering for themselves what lies at the heart of that tradition. In other words, all great pianists do more than just play according to tradition. They create one.

BUZ: On top of that, there is theory. I had a pleasure of attending one of the lectures at your Festival, by Alan Walker1, who presented a fantastic analysis of Chopin’s genius and advice on how to play his music. He talked about a perfect balance between the composer and the pianist’s personality, and according to him, the most fundamental rule of interpreting Chopin’s music is not to break the “11th Commandment,” which he defines as: “Thou shall not fool with Chopin or else he will fool with you.” Do you subscribe to this recommendation?

KK: Absolutely. That is precisely what makes interpretation of Chopin so challenging. His music has a certain fragility. If you push and pull just a little too far, things simply break down. For other composers of the Romantic period—Schubert, Schumann, and Liszt—pushing or pulling too much might actually be encouraged according to Romantic standards. Chopin was rather enigmatic for his time because of his deep interest in the music of the past and his love for Classical principles, for Handel, for instance. In 1829, in one of his letters, he wrote that Handel’s music was close to his image of what he considered to be ideal music. He was not a proponent of the principles of his Romantic contemporaries, which pushed for more individuality and extreme emotions. Chopin was so much more interested in the values of Classicism—the purity of sound and balancing of structure. He was also interested in the early Romantic Italian bel canto opera, which had so much to do not with power and forceful sounds that project through the entire theater, but rather with subtle, delicate phrasing and beautifully controlled singing. If one injects too much of their personality, this can destroy one of the core aesthetic values of Chopin’s music.

BUZ: Professor Walker talked at length about human voice and its connection to Chopin’s music. You should learn to sing to play his music well, he said.

KK: There are good and bad singers [laughs]. It is very useful to learn to sing and to work with singers. One should also remember that when Chopin employed the vocal techniques of the 19th century, what he really valued was the control of the voice and the beautiful embellishments of the bel canto-style singers.

BUZ: And then there is breathing and phrasing.

KK: Correct. Great singers can breathe in such a subtle and beautifully controlled way that we don’t even realize that they are breathing. Chopin himself said that the lifting of the wrist—not the whole arm—was the mechanism for breathing in piano playing. There needs to be this subtle flexibility in music, just like in the limited rubato Chopin spoke of; if you blow the candle too much, you will blow out the flame entirely

BUZ: This year you released a recording of solo piano works by another splendid Polish composer, Ignacy Jan Paderewski, which you performed on his own 1925 Steinway.

KK: I fell in love with that instrument. However, I have to say it was quite a challenge to play it, especially performing large-scale compositions like the sonata and toccata, which are pieces that demand power and clarity. The hammers are larger than in today’s Steinways, and the tone was quite mellow and better suited for works that have a lot of melodic quality. There was something mature, ripe about that instrument; it lacks directness and felt burnished. I must say that after the first day of recording, my hands were almost bleeding [laughs].

BUZ: After your concert in 2011 that featured works by Paderewski, the reviewer described it as your “homage to the tireless energy and spirit of the Polish people.” Last February you played Paderewski again, this time at Carnegie Hall to celebrate the 100th anniversary of Polish independence. What significance did this concert have for you?

KK: Apart from the fact that it was actually the first time that I performed at the Stern Auditorium (I had played at Carnegie Hall before, but never at Stern), it was really a special moment to be playing on the same stage on which this great pianist played. I felt I was transported in history. I have nothing but the greatest respect for Paderewski, not only as a musician but also as a man, as a statesman. He was remarkable. He even offered to pay off his country’s national debt with his own money! There are few politicians today who would do that. And I love his music. So to be able to perform on the stage he loved so dearly and where he often played was such a great honor, and I will remember this as a special moment in my performing career.

BUZ: Paderewski is one of the few classical musicians who got involved in politics, and his role in Poland’s gaining independence is unquestionable.

KK: He was never interested in politics per se. He was living during the times when it was inevitable. He was simply interested in seeing his country not being destroyed and existing as a state. I think politics was not something he particularly enjoyed or sought. He did not have a great desire to be a prime minister of Poland, and it certainly did not last very long. He loved his nation and felt the obligation as a person of repute, of great success and means to use his gifts for the sake of his people. That’s what I love about him. He was more than just a patriot. He believed in the brotherhood of humankind, as did Beethoven. I believe that is why so many people loved him, because he was a human being in the highest sense of the word.

BUZ: Paderewski was significantly influenced by Chopin. Where can we see the traces of the great master?

KK: It is all over the place. First of all, it is the essential “Polishness” of Chopin’s music, which we find in Paderewski, too. Also, he wrote the same forms, such as krakowiak, nocturnes, and pieces that have references to Chopin, not to mention that both Paderewski and Chopin grew up in Poland, then lived far away from the homeland they so longed for. In addition, there is something improvisatory about Paderewski’s compositional style. When you look at his score, the music changes all the time; harmonies are rarely repeated in sections that normally should repeat. He would often perform his music differently from the way he had written it down. It helped me actually understand something about Chopin. That is why we can find different versions of the same work, for example the Waltz Op. 69, No. 2, in which the French edition has significantly different harmonies and rhythms from the English edition. I don’t think either Chopin or Paderewski heard their music in an idealized final form. What we have in their scores are more like sketches or snapshots of a potential interpretation. When I interpret Paderewski, I really try to explore the ideas that are on the page, but I never limit myself to merely what I see. I make quite a few small changes, within the style, of course. I do the same with Chopin’s music, especially with his earlier works. I think these small embellishments or alterations can actually benefit the score and give it greater authenticity. Being completely faithful to the score means more than just playing the notes that are there. In the same way, to not embellish certain passages in Mozart would be contrary to performance practice and counter to his performance style. So I think in this respect, Chopin and Paderewski have very much in common. Their music is very fluid—constantly changing.

BUZ: Have there been any composers since Paderewski who have carried on this tradition?

KK: There were contemporaries to Paderewski who carried that tradition, Rachmaninoff being the greatest. As a pianist he was superior to any other pianist of that time. You hear that freedom and improvisatory quality in his recordings; he does not follow his score particularly closely. After that, you could say that Horowitz belonged to the same kind of thinking, as did Earl Wild, although he was less a composer than an arranger. In Wild’s recording of Paderewski’s Piano Concerto in A minor, Op. 17 you can notice clearly that he takes a lot of liberties, liberties that I think Paderewski would have approved of. Unfortunately, most pianists of the 20th century took a different path. Especially after World War II, the piano world almost sterilized itself; it devalued many of the special qualities that existed in the golden age of pianism.

BUZ: Other forms of music, especially jazz took over that aspect of freedom and improvisation.

KK: Agreed. Chopin and Liszt and many pianists of the 19th century knew how to improvise on any given themes, mostly operatic themes, which were the “standards” at that time. They were the jazz pianists of that age. All jazz musicians know how to improvise on the standards. Leszek Możdżer2 is a wonderful example of a pianist who was trained as a classical pianist and moved to jazz when he finished his studies. I performed with him at a concert themed “Chopin Correspondences,” in which I played certain loops of Chopin themes, and he would improvise over me on the other piano. It was quite extraordinary to listen to the manner in which he heard music. What I found remarkable was that unlike some jazz pianists who have good technical abilities but are limited in areas of tonal color, Leszek Możdżer has such a great sensitivity to those subtle tonal varieties that remind me of Chopin’s tonal world—this delicate quality, purity of sound, an ever-changing palette of colors.

BUZ: I understand that the Frost School of Music has an excellent jazz department

KK: Actually, it is one of the most widely respected jazz music schools in the country. Its faculty has had many accomplished musicians, like Pat Metheny, Gonzalo Rubalcaba, and Shelly Berg, for instance. I encourage my students to learn the principles of jazz because it can have a beneficial effect on their interpretations. Being a good jazz pianist involves strict discipline of understanding harmony and progressions, and inversions, and how particular melodies can be embellished in certain ways. I think that in the next generation, there is going to be a renewal of the improvisational skills that existed in the 19th century. Pianists will be either interested in learning them or perhaps required to employ them. I was recently judging at a Chopin piano competition in Darmstadt, and they introduced—still optional—an improvisational round, with a special prize for the best improvisation. Things are changing in the music world. Another revolution, if you will, is the revival of the interest in period instruments. More and more pianists are looking into the past for a discovery of new interpretations inspired by those instruments. We have seen it with other instruments, with ensembles. Who would now go to a concert of Bach on modern instruments? It is demanded by the audience, because once you have heard this authentic sound, it is difficult to get it out of your system.

BUZ: Is this a reaction to the ever-present digitalization? Haven’t people grown tired of the perfect-pitch, auto-tuned sound, purified by the mastering process?

KK: This is a good observation. As I said earlier, the modern music world sterilized interpretation in many ways, and we demand from modern performance qualities that were completely foreign to the musical values of the 19th century, such as control, evenness, consistency. The rise of the recording industry may have something to do with this. If in the 19th or 18th century a musician played everything evenly and consistently, that musician would be considered very mediocre. Period instruments are fascinating: each of them is so different, and they all have their own personality. No two Pleyels or Erards are the same. Each instrument has its own particular tone and must be approached uniquely, individually. When a pianist plays those instruments, you begin to hear that distinctive sound, and you really start to discover the composer anew, to get into his mind. This new interest in history is on fire. Certainly, it is on fire with me!

1 Dr. Alan Walker (b. 1930) is an English-Canadian musicologist, Professor Emeritus of Music at McMaster University, Canada, known for authoring a three-volume biography of Franz Liszt and Chopin’s new biography Fryderyk Chopin: A Life and Times (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, October 2018).

2 Leszek Możdżer (b. 1971) is a renowned Polish jazz pianist, music producer, and film music composer.