Trying to Describe the Shape of Air

Exclusive Interview with

Joyce Yang

By Bożena U. Zaremba

The list of awards you have received is remarkable. Which do you cherish most?

The prize that really changed my life was the Van Cliburn Silver Medal in 2005.

That came as a surprise. I had entered the competition thinking it would be a great experience for me to gather such an extensive variety

of music on that level. When I walked away with Silver, I had to become an adult overnight, a professional artist with a very distinct voice.

I was just a second-year student at Juilliard, and till then I simply played the music I loved. Now I had all these high expectations behind me, I was doing interviews, and I had to define my music, not only through my performance but through words.

Handling all the attention and adapting both musically and emotionally to the situation was a big challenge.

Some musicians say that the most important part of a competition is the preparation, and if they receive a prize, it is just an icing on a cake.

Was this the case with you?

The preparation process was long and intense. For a 19-year-old to prepare two solo recitals, two concertos and two chamber music pieces in ten months is quite a demanding task. It was a journey in which I had to transform to a different level of artistry. The prize was a turning point and a pinnacle of all my efforts. It was also very rewarding to be appreciated for something I didn’t even know I had in me.

Can you tell us how it all started?

I was four years old when my aunt, a piano teacher who believed that the instruction needs to start at an early age, convinced my parents to buy a piano for me. She became my first teacher and really my best friend. Most importantly she made me appreciate the instrument. She made the whole learning experience very attractive, and the piano became the greatest toy I owned. I never had to be forced to practice; I didn’t even know it was practicing until much later. It was a fascinating process. Then I played for my parents and my relatives, and they were so shocked at all the things I could do on the piano. I got a lot of support and a lot of appreciation, which gave me a boost to move forward. It was like that until I was around ten.

Was it only after you moved to the U.S. that you realized it was much more hard work than you had imagined?

In a way, yes. At the age of nine my mom brought me to New York for the first time. I was introduced to Yoheved Kaplinsky, who eventually became my teacher for the next 14 years. I got an audition with her by sheer coincidence, and she said she would teach me if I could be here. My mom, who is a molecular biologist, was doing a sabbatical, and she agreed that we would stay in New York for a year. I would take piano lessons, learn a bit of English, and then we would go back to Korea. But at the age of 12 two prominent things happened: I won a competition in Philadelphia, which got me to play with the Philadelphia Orchestra, and I played at the Juilliard benefit concert. During the dress rehearsal for that concert, I was asked to join their roster, so, 12 years later, here I am. It seems that things always happened earlier than I thought they would. But coming back to practicing, it was never stressful, and it still never is. I never practiced that much, maybe three hours a day growing up, and now five hours. But it is five very intense hours. It is a creative process, figuring out what is right for the moment, what is intended by the composer combined with my own inclinations. To have that ability is extremely rewarding, and I know that without practice it can never happen.

Have you had life outside music?

I always had friends growing up. We played, went to the movies. I did have a childhood and never felt I was sacrificing anything. It was my parents who made sacrifices. My mom was here with me for 12 years because I was too young to be on my own. That is dedication.

In 2006 you performed in your home town in South Korea, which was described as a “triumphant return.” It must have been very special for you.

It was unbelievable. It was like a wedding reception without a groom [laughs]. Probably every single person I had ever met in my life or my parents had ever known was present at that concert. Hundreds of people came up to me and said, “I knew you when you were three” or “I saw you the day you were born.” For my family, it meant so much. For me, it was a proud moment. It felt like I was giving them this gift and showing them that this has been my journey. I felt that this way my efforts were validated. Of course, it was a great experience working with Lorin Maazel. There was so much trust. We took chances, and as a result, wonderful, spontaneous things happened. I was just floating in the air.

You have performed with top orchestras and conductors. What does it take to collaborate with other musicians successfully?

The same classical musicians are given the same notes, but we always alter the music with the energy level that we have at that moment, building tension here, releasing it there, building it up to a climax, then relaxing again. All these decisions are made during the rehearsal, when we try to feel each other and understand each other’s instincts. It would be nice if I could just do whatever I feel like and the orchestra would respond perfectly, but that’s not the case. It is not what music is all about. It is two (or more) different minds coming together; it’s a “call and response” kind of a conversation. When musicians are similar enough and open-minded enough, after a while, with extreme artistry coming from all ends, there is a moment when it all comes together and it becomes completely inevitable what we are doing next. I think only great orchestras can accomplish that. A mediocre orchestra will rehearse a piece a thousand times and in a concert will try to duplicate exactly what they did during the rehearsal. For a great orchestra, on the other hand, rehearsal is just one way of doing it, and they can just change as a group in an instant. We shouldn’t shy away from our instincts. As a soloist, I am extremely open, and maybe that spontaneity, that readiness distinguishes me from other soloists. I remember Maazel saying after one performance, “We’ve achieved freedom today.” That freedom means to be able to take off in any direction we feel like going, because the moment asks for it. Only fine musicians can achieve that freedom in a split second. It is a thrill. It is magic.

What about a solo recital?

During a recital, I have just my own ten fingers, which is like having ten different instruments in me clashing against each other or coming together. I am one, and I have to separate into all those entities. That is a much bigger challenge than a concerto. A recital is a long, draining process, exploring every side of you. You pose a question, and it is you who answers it. It’s like talking to yourself.

One critic described you as “a powerful player, with the accuracy of a surgeon and the heart of an artist.” How would you respond to that?

I would love to be that [laughs]. The heart, I have. And my heart is always ahead of my mind. I cannot help my heart from going a certain way, and I can never make my mind stop the heart, not in music at least. I think it is a very Dionysian trait. So there is a lot of passion. I do it with conviction. The surgeon part is great because that means I practice enough so that my fingers can follow my heart.

I can see a little bit of a surgeon’s mind in the way you talk about music. It was fascinating to listen to your analysis of Bernstein’s Age of Anxiety, or Schumann’s Carnival. What a terrific insight! Do you study every piece you play with such scrutiny?

I try to. I have great curiosity about the pieces I am going to play; I think I should understand them in order to produce the maximum effect. But I am not a book nerd. I can recognize a masterpiece that does not have any meaning besides how it sounds.

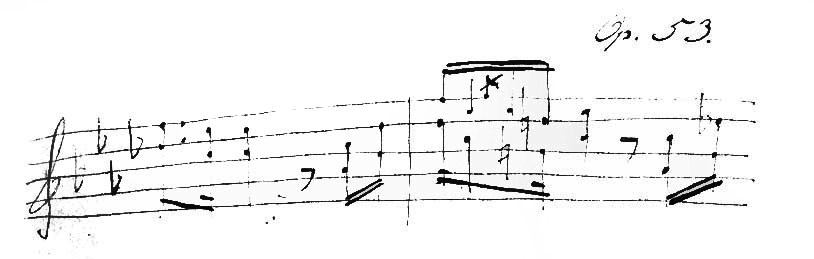

It would be interesting to hear you analyze Chopin’s music.

Chopin’s music is very hard to describe with words; it is so organic. I have a case of synesthesia. That is, I envision the sound in colors and shapes, and I find Chopin’s music very difficult to put a picture or shape to. It’s like trying to describe the shape of air. It is such a challenge.

What place does Chopin have in your vast and versatile repertoire?

His music is very personal. In his more intimate pieces, like mazurkas or nocturnes, he pinpoints the kind of joy you feel when you are totally alone. While playing his music, I feel like I am always trying to grasp the emotion that I feel while I am by myself, rather than something you would share with other people. His music has incredible power. It draws you in. It comes to you like air, enters your system and takes you to the place that is familiar only to you. It cannot be expressed in words, because as soon as you say it, it’s over.

You have just graduated from the Juilliard School of Music, where you studied not only music, right?

Yes, I also went through all the humanities courses, which I think is important. For example, I took a class in creative writing, which helped me discover poetry, and now I just can’t get enough of it. I think that humanities courses and reading all that mind-provoking literature made me think. I am grateful for that. I absorbed whatever I could, given the amount of time I had, which wasn’t much, because of all the concerts and engagements. It was a hard process. But I am glad it was part of my life, and I am glad I’m done [laughs].

What, in your opinion, makes that school so unique?

I think the determination among students is incredible. Everyone has a direction and knows what they want to be and what they want to say, and they are all ready to go out to the world and make it. You enter the school on the fourth floor, which is filled with hundreds of practice rooms, and none of them is empty. And as soon as there is one available, we are like vultures trying to get in. People would go there in the morning and stay all day. You feel that drive in the air. Being in that atmosphere wants you to be the best you can be.

What about the teachers?

I had only one teacher, Ms. [Yoheved] Kaplinsky, so I can talk only about her. The greatest lesson I learned from her is to be an individual. In studio classes – the master class type of setting – we used to get together to play for each other, and she would comment at the end, guiding us through the process, telling when it was in bad taste or not right. Somebody could be playing the same piece I was playing and yet sound totally different. She always helped us find our own voice. Sometimes she might say, “I do not agree with everything you’re doing, but you are the architect of your own building, and if I were to take out one pillar, the whole building might collapse.” For me to realize that this was my own creation was the greatest compliment. If she said, “It’s not really convincing,” that was really the final testimony. I always relied on her opinion. Without her I have no idea where I would be today, and I am grateful for her guidance.

Are you ready to be on your own and rely on your own judgment?

It hasn’t hit me that I am done yet, but psychologically I am ready for the next step. I am ready to be self-sufficient now.